Review of CANCER VIXEN by Marisa Acocella Marchetto

Review of CANCER VIXEN by Marisa Acocella Marchetto: A Strong Sense of Girl

Some time back, I got an e-mail alerting me to the existence of a graphic novel called CANCER VIXEN. I say "graphic novel" but that's a slip, because it's actually a memoir rather than a novel. A memoir in comic book form. A breast cancer memoir.

Think of MAUS, the Holocaust cartoon featuring the genocidal Germans as cats and the victim Jews as mice, and you get an idea of the quality.

What soon struck me, as I began leafing through the pages, was the strong sense of girl which came through to me. It's a cartoon book which is very much about a woman's situation, facing breast cancer, a potentially fatal disease, when she's 43 years old and is scheduled to get married, and to get married for the very first time, real soon now.

I can't draw at all, so I was really mind-boggled as I thought of how much work must have gone into all this, page after page after page of stuff.

I personally do not expect to find myself ever facing breast cancer, though it is a fact that men sometimes do, since the breasts of a male replicate, in large measure, the physiology of the female.

What is really interesting is the peek it gives me into the world of a woman. This, after all, is a woman who is very much focused on self-assessment, wargaming her situation and, constantly, assessing the people around her.

The book opens like this, putting you in the picture (no pun intended):

"What happens when a shoe-crazy, lipstick-obsessed, wine-swilling, pasta-slurping, fashion-fanatic, single-forever, about-to-get-married big-city girl cartoonist (me, Marisa Acocella) with a fabulous life finds A LUMP IN HER BREAST?"

After that text, we see a picture of her swimming. This is how the cancer showed up: she was swimming and started to wonder why her arm was hurting as she swam.

Already we're into a different world, wildly remote from mine. My one and only lipstick experience involves accompanying my sister and one of her friends to a lipstick shop near the Devonport cafe where we had been having a coffee break. I was staggered by the price these women thought reasonable to pay for a tube of lipstick. I mean, we're just talking about crayons for the lips, right? And how does someone get away with charging that much for what's really just a skin crayon?

Hence, right at the start, there's a strong sense of girl.

Marisa is an intense observer, really cued in to the social dynamics of her situation, much more than I am in situations where I'm the patient. She comes up with stuff like this:

"100,000-watt smiles #2 and #3, now I KNOW I'm in deep ..."

A little later on she comes out with this:

"When a doctor turns his back to you, it's never a good sign."

She's been watching, mapping, picking up on the secret signals. By contrast, I went through my own cancer experience as a sleepwalker.

The laconic wit of this exchange appeals to me:

Very loud friend: "You've NEVER had a mammogram? I'm going to kill you!"

Embattled cartoonist: "Thanks, but I'm doing quite well in that department."

And now, quite early into her graphic memoir, she's into a dialog with her disease, a hooded figure holding what looks like a sickle, hooded but showing enough of the face so that we can see that there is no face.

And she says:

"Listen, Cancer, ya sick bastard ..."

The capital C for "Cancer" is my choice, since the cartoon text at this particular point is hand-lettered in capitals.

In the next frame we see her marriage thoughts:

"I want a dress that's simple and white and kinda tight."

That's something I've never thought about, not once, in the whole fifty years of my life. What kind of wedding dress do I want? Thought never crossed my mind. Not even once. Even though I did end up getting married, twice.

Now she's facing up to the fact that she has to tell the guy she's going to marry that she has this problem. It's very much a girl moment, a behavioral pattern beyond the imagination of the average man:

"I put on 'brave' lipstick by M.A.C. I needed something, anything, that would help me face God willing my future husband ..."

The lipstick, hugely pink, dominates the left side of the frame.

When I began reading CANCER VIXEN, I had one brain-damaged moment when I hit the problem of what an s-mother might be (written "S-MOTHER"). Then I realized that this is her mother who smothers her, so it's a pun, mother/smother.

In one of the early frames, the smother says to her daughter "And you'd better not draw me on the throne." The smother is phoning from the toilet, as we see in the frame a decorative sign saying "LA TOILETTE," so the daughter is flirting with the attractions of insolence, though we don't see her seated on the throne, but, rather, just see the extreme edge of one side of the toilet.

This cartoonist, it emerges, sometimes draws real people into the cartoons that she has published in (I think I have this right) THE NEW YORKER.

She includes what I think is one of her New Yorker cartoons in CANCER VIXEN, and it's drawn a lot smoother. Her own CANCER VIXEN frames have a lot more jerky energy, and she's an energetic innovator when it comes to the business of finding different things to do with the frames.

All in all, quite a good read, and, as indicated above, there were some parts that I found fascinating.

As we take the trip through Marisa's life, we get little glimpses of the people she meets and works with, and little insights into her life. For example, an artist NEVER has a pen that works. Drew, one of her editors, "EATS GUMMI BEARS FOR LUNCH." (I've left the text in the original caps because we don't have GBs here in Japan, so I don't know whether they are or not a brand name and therefore don't know whether "G" and "B" should or should not be capitalized.)

More detail on Drew: when it comes to GBs, "He prefers cherry."

This kind of details builds the reality of a New York life, taking us through the postcard images (Empire State Building, World Trade Center) to the lived life where your pen can't be found in the wretchedly black interior of the handbag (why do they make the insides that color?) and your editor is a GB junkie.

Girl talk, three girls together at a restaurant table, no males in earshot:

"Well, I was thinking of getting my nasal labials done."

Reaction of non-cued-in male reader:

"Huh??!"

... and then, after the girl stuff, the gossip life, the ravishing restaurant, suddenly we're into 9/11, and she has just been woken up at 0847 by a LOUD plane ...

And, as the day evolves, she's sent lurching right into Ground Zero, at her editor's behest.

She's been blasted out of the fashion bubble and right into the heart of Deep Seriousness.

And was being at Ground Zero why she got breast cancer? Well, that question launches her into the cancer guessing game, and here her story becomes familiar. Yeah, you get cancer, you wonder why. You want a reason.

In due course, after we're done with her love life, we get to her course of treatment. We follow the treatment, step by step, and finally arrive at the penultimate page, page 135 of 136, where she gives a statistical sum-up of what she went through and what it cost her.

What it cost, in financial terms, was US $192,720.04. My own medical expenses in the New Zealand state-funded system were more modest. All up, I think I ended up forking out about NZ $5,000, rather less than five grand American, split between one for-profit MRI scan and one for-profit cataract operation. When it comes to money, I can't compete.

In this situation, I shouldn't be having competitive thoughts anyway, but it's my nature, and I can't help it.

Needles, though, I can definitely compete. She's kept track of how many needles she had, and they added up to 29. That struck me as amusing, that she had undergone so few needles that she could keep track of them all.

How many needles did I have? I have no idea. I don't even know if I can add up all the places where I had needles.

The very first needle would have been at the Tokyo Medical Center where, eyesight trouble having cued me to the fact that I had something which needed a diagnosis, I had the first needle as part of a test for diabetes, which proved negative. And, over the next couple of years, I had more needles at that clinic, though I can't remember how many.

My first Japanese hospital was next, in a part of Tokyo called Mitaka, and there I had more needles than I can count, including one to inject me with iodine, one to inject a radioactive isotope of gallium, and one, to inject steroids, into each eye. When they start sticking needles into your eyes then you know you really are in serious needle trouble.

What I didn't have, but should have had, was a needle to inject the rare earth gadolinium on the occasion of my first ever MRI scan of the brain. No contrasting dye was used, and, if you're looking for lymphoma, which the doctor was, an MRI is useless without it.

The next place where I had a needle was the for-profit MRI center down at street level at Auckland Hospital, where they did inject gadolinium.

Then, at the oncology ward, I had a needle into the theca, the sheath of the spinal cord. My first lumbar puncture (or, if you prefer, spinal tap). As with the eyes, when they're probing needles into the area which holds your body's all-important broadband connection, you know you are in very, very serious needle territory.

Later, when I had neurosurgery, there were more needles, including one to put me under and another, given while I was out, to give me morphine to kill the pain.

There was also another needle to the eye when I had my first vitrectomy, a jelly-removal operation on the left eye which was carried out in the extremely ancient eye clinic section of Auckland Hospital, which I think is now no longer used, at least not as an eye clinic.

The diagnostic process having been completed by brain biopsy, I had six cycles of high dosage methotrexate in the hematology ward, and each of those involved a bunch of needles. I also attended the hematology daycare ward for more lumbar punctures.

In between times, I showed up at a medical laboratory in Devonport for more needles, each to do pre-chemo tests.

Later, there was another needle into the eye for my first cataract operation at the Northern Clinic, and this needle, into the left eye, required a lot of effort on the part of the anesthetist, who had to shove the needle through scar tissue left by the vitrectomy. He described this process as "challenging." Fortunately, because a topical anaesthetic had been administered first, it didn't hurt.

Another needle into the eye followed at the Greenland Clinical Center, where I had a combined vitrectomy and cataract operation on the right eye.

Remission having been achieved, I went back to the dentist who had put in a temporary filling some months previously, after I broke a tooth while eating spaghetti, and did a crown (or, if you prefer, a cap) which had been deferred until I was done with chemo and radiotherapy.

For this, he needed to use a needle to inject anaesthetic. He commented on the fact that I showed absolutely no reaction to having my gum probed with a needle. I asked, well, do people usually react?

"They usually show some kind of reaction," he said.

With cancer seeming to have returned, I went back to the oncology ward. Another MRI, another needle. And then one more lumbar puncture.

When I was told, okay, relax, it's not cancer back again, it's just your eyesight has been trashed, tough about that, no undoing it, get used to it.

With that helpful news having been delivered, I returned to Japan and had my next needle at the hospital in Yokohama that I'm calling Meijin Hospital, one needle to draw about six vials of blood.

That hospital's MRI facility was booked months in advance, so I was sent to a private MRI center, the procedure done under the Japanese national health scheme, and there was another needle for contrast.

Back at Meijin Hospital, I had more needles for repeat blood tests and yet another CT scan, my third CT scan with injected iodine, as there had been one of these in New Zealand.

Yeah, I think I can out-compete on needles.

I can't remember, then, how many needles I had. I'm not even sure that I can accurately remember all the different places where I had needles. Some went into my spine, so I couldn't observe them. But the ones that I could watch I did, finding it interesting to see the steel slide into my veins, which were pretty good veins when I started out, but which were pretty much junkie territory by the time I was done.

One guy who read my medical memoir CANCER PATIENT e-mailed me and asked why, during my treatment, I had a ghoulish desire for photos (or, ideally, video) (neither of which I ever got) of medical procedures, such as my lumbar punctures and eye operations.

The answer is that being a patient is, above all else, as boring as all hell. Boredom trumps terror ten times over. And so, when something is actually happening for once, like a needle being stuck into you, it has an entertainment value which most of the process lacks.

My own experience is reflective of my character, which is introverted, and, during the whole cancer process, I became more and more self-focused, losing interest in the wider world.

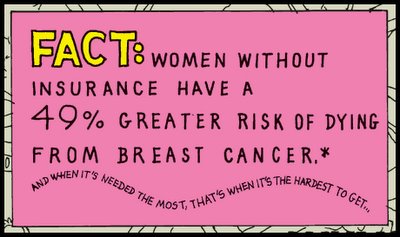

For Marisa, who evidently has a sunnier temperament than mine, having cancer seems to have turned her thoughts outward into the wider world, as, in the course of her breast cancer memoir, she considers wider issues, with one page of the book highlighting this fact:

"Women without medical insurance have a 49% greater risk of dying from breast cancer."

Welcome to the United States of America, land of the free, beacon of liberty for the nations of a world not so fortunate.

Working my way through this graphic novel (yeah, I think it qualifies as a novel, even though it's technically non-fiction) I catch small signs that it's written out of a specific culture, that of the USA.

Marisa draws a picture in which her inamorata, Sylvano, honors her by having one of the precious tables in his upmarket restaurant (the kind of place where, if you want a table, it helps to be Madonna) marked with three cards. One says MARISA, one says SILVANO, and the third says RISERVATO. Marisa pens an orange cartoon bubble pointing at the foreign word to explain it: ""That's "reserved" in Italian"". Yes, we're definitely in the famously monolingual United States.

When she finally moves into his apartment, which takes her two months, she discovers something that surprises her: shoes. Bubble: "He's the only straight man on the planet who has more shoes than I do!"

While there's a little bit, here and there, which reveals fractional insights into America, there's lots and lots and lots and lots about World Girl, the foreign planet that I will never visit.

Once she's got her paws on the most desirable man in New York city, the grapevines is alive with the chatter of the sour grapes. Not all of this behind her back. One woman comes right up to her, confrontationally:

"I'm a model. How did YOU get him?"

In the realms of her imagination, Marisa goes hypermuscled superhero and trashes the importunate model. In the real world, she behaves herself. This peek into a girl's mind suggests that sometimes the mind of a nice girl can be every bit as violent as mine.

New York adult-to-adult exchange, when he proposes:

Sylvano: "There's the ring."

(He's already told her it's an engagement ring.)

Marisa: "You won't get on your knees?"

Sylvano: "C'mon, open the box."

I could go on quoting, but I think I've said enough. To sum up, this is a pretty cool book, a peek into the life of a big city girl in New York city, a venture into the realms of breast cancer, and, above all else, access to the mysterious world of Planet Girl. I recommend it.

There's a link to the read-for-free-online version of the book on this web page, on the right. Also a link to the short promo video at cancervixen.com, worth twenty seconds or so of your time, if you have that much time to spare.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home