Life After Brain Cancer

Life After Brain Cancer

Life After Brain CancerLife after brain cancer: the reality of living with brain damage: survivorhood following brain cancer, neurosurgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

The photo at the top of this blog entry, assuming that I have succeeded in uploading it, shows my curly-haired daughter Cornucopia, age two and a half, sitting in our elite Silver Cross pushchair (or, if you prefer, stroller).

The photo clearly shows the big road-conquering wheels, four sets of two wheels, ideal for the twice-daily commute we have to make to the daycare center, which bumps us over curbs and metal grilles.

The photo was shot indoors on Sunday 17 December, the day we took the Silver Cross out of the long thin cardboard box in which it was delivered.

(Cornucopia used the long narrow box for a tightrope act, and was doing very well, and was very pleased with herself, until she abruptly fell off and began wailing.)

My wife, who knows how difficult I find it to get to grips with new things, patiently explained how the pushchair was to be unfolded and then, afterwards, folded up again. (It gets folded up when at the daycare, where it sits, along with other folded-up strollers, in a small penned area where domesticated strollers are kept.)

I am a mechanical idiot and always have been, but the mechanism of the Silver Cross was lucid, admirably simple, and I thought it would be no problem to attain total mastery of this device.

Even so, once I was absolutely sure I knew how it was done, I went through the sequence three more times. Unfold it (being careful not to mash Cornucopia, because it unfolds in a big hurry). Then fold it up again.

Unfold, fold; unfold, fold; and, third time for luck, unfold yet again and, once more, unfold, so it is open again and ready for use.

We took the pushchair to Shimomaruko to visit the parents of the two-year-old twins Yui and Kai. And, the next day, Monday, I took Cornucopia to the daycare center in the brand new pushchair for the first time.

The handles are higher than those of our worn-out secondhand chair, which means that my wife does not have to bend when pushing it, which saves her back.

I never had to stoop over to push our previous pushchair because my arms are the long ape-like arms of a member of the Caucasian race, which are significantly longer than the comparatively shorter arms of the average Japanese person, the Japanese having evolved further away from the ape than have we Caucasians.

(In consequence of the evolutionary difference, I cannot buy shirts or jackets off the rack when I am in Japan, but have to get them tailor-made if I want stuff that will fit.)

The high-standing handles of the Silver Cross, which allow plenty of space between the chair and the person pushing it, also mean that I do not have to cramp my stride. Instead, having by now largely recovered from the physical insults of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, I can step out at my normal pace, which is precisely 110 steps a minute, reliably covering 100 meters in a minute, one kilometer in ten minutes, and six kilometers in an hour, regardless of the terrain (unless the terrain is that of the high Himalaya in Nepal, in which case you may find the six kilometers of your choice to be a full day's trekking).

We got to the daycare in great style and then I found I could not collapse the pushchair so it could be folded up and stowed away.

I knew there was a handle on the right that you pulled and I found the handle. But it was not engaged with anything. Looking at it, it clearly had no mechanical function.

The clock was ticking and I had a train to catch, so, finally, I parked the pushchair by the stroller pen and carried Cornucopia to the daycare's door. (Carried because she is often reluctant to make the journey to that door.)

Outwardly I was calm, but inwardly I was seething with almost uncontrollable rage, baffled by the fact that the chair, which had seemed so lucid while I was playing with it in the sheltered environment of the living room, had become a fathomless mystery when it was set loose in the real world.

I said goodbye to my daughter and stalked off in the direction of the station. En route, I suddenly realized what brain-damaged error I had made.

Robotically, without thinking, I had gone through the procedure with which I had programmed myself on the preceding day. Open up the collapse pushchair, set it up so it is ready for transportation, then collapse it again.

My programming had failed because, when I started, the pushchair was already ready for transportation. I was trying to initiate by using the procedure you need to unfold it, but it had already been unfolded and set up for action.

I turned on my heel, strode back to the daycare center and took another shot at collapsing the pushchair. I found a strap at the back which I pulled upwards. Then I remembered that I had to do something with a foot pedal, so I found the pedal and pressed it with my foot. (Not exactly a pedal, more a lever that you can push down on with your foot.)

The pushchair refused to collapse.

I was running short of time so I strode back toward the station, rapidly. When I was almost at the station, I realized my error.

The foot lever is used as part of the setup procedure which readies the Silver Cross for action. It locks the collapsible part into rigidity for transport.

My thesis, now, was that to collapse the chair I should simply tug up on the strap that is attached to the framework at the back, thus unlocking the framework and allowing the chair to collapse.

But I was out of time, so had to hurry to the train and get on.

Once I was on the train I got my bottle of water out of my pack and drank some. My throat was dry.

Although I can now walk pretty well and even run a little, my body chemistry has been trashed by the chemo, and, whenever I am under stress, my throat starts to get dry. I was stressed out now, and so needed water.

During the day I thought, from time to time, about the chair. I contemplated experimenting with collapsing it at the daycare. But, when it was time to uplift my daughter, I simply went home with the chair as it was, without making experiments.

The chair lives down in the garage, set up and ready for use, and I figured I was safer leaving it as it was, and making a fresh attempt at collapsing it to fold it up when I pushed it to the daycare center on the following day.

That evening, at dinner, my wife asked me how the pushchair had been, and I told the truth, which was that it had been just fine, and had easily conquered the lumps and bumps en route.

My wife then asked me if the chair had been too wide.

No, it had not. It is wider than our previous stroller, and I had been worried about the narrow choke point where you have to get past a utility pole which is very close to the bank at the side of the road. Going wide of the pole is not an option because, for the sake of safety, you have to stay inside a barrier set up to separate pedestrians from the cars on the busy road which part of our route follows.

I said nothing about the problems I had endured in trying to collapse the pushchair, because I was confident that I had this problem licked, and that the chair would collapse without a problem if I simply used it as it was designed to be used, and yanked on the yanking strap, which unlock the hinged metal framework at the back, then collapsed it.

And so it proved.

Sort of.

En route to the daycare center in the morning I mentally rehearsed for the Confrontation, reminding myself that there are two separate procedures, one to collapse the pushchair and the other to resurrect it, and it is not appropriate to mix and match the steps from the DOWN procedure with the UP procedure.

When it came time to collapse the chair, I confidently took hold of the strap at the back and yanked upward. Then put pressure on the chair, expecting it to collapse. It refused to do so.

The day before, I had pushed at the lever on the right, thinking it would collapse the chair. Instead, the frame had remained rigid, so I had formed the thesis that this lever was used to lock the frame rather than unlock it.

In the face of the chair's obstinance, however, I revised my theory.

Looking closely at the chair, I saw a lever optimally placed for foot use, vertically below the strap which yanks the framework upwards. THAT was the foot lever.

Which meant that the lever on the right side, halfway up, was the hand lever.

The day before, hand pressure on this lever had failed to unlock the framework. But, with my revised thesis driving me, I applied more pressure to the hand lever, and the hinged metal framework, which had locked rigid, unlocked compliantly, and the chair folded.

Again, sort of. It did not fold into the neat package I had expected, did not squash down into the optimally compact shape, but it did crush down enough for me to corral it into the pushchair pen.

At the end of that day, Tuesday, when it came time to unfold the chair, there was no catch to undo, since I had not managed to squash the chair down enough for the catch to engage.

So I simply stood the chair up and it unfolded without further coercion. Then I found the convenient foot pedal, the foot lever down at the bottom of the chair, and pressed. And the framework neatly locked rigid.

An immaculately designed piece of hardware, this chair, if you ask me.

But, as indicated, getting to grips with its simplicities was no simple matter, because the two options, UP and DOWN, had jumbled their instruction sets in my brain, and untangling them again had not been a straightforward matter.

Still, I had done it. I was the triumphant master of the Chair That Could And Would, and I pushed it confidently homeward through the darkness of the winter night, until I started finding trashed newspapers underfoot, and realized that the curve that the road was making was unfamiliar, and that I had, for the first time ever, overshot the turnoff to the left, missing the road which I had never missed before.

When I finally got Cornucopia and the chair back to the garage which sits beneath the house, I found I was singing, to the tune of FRERES JACQUES, "We were waiting, we were waiting, waiting for the green light, waiting for the green light, we will cross."

Once again, I had mixed and matched, illegitimately. The "we were waiting" version is the one that you are supposed to sing AFTER you have successfully crossed the traffic-light-guarded pedestrian crossing, and it should end "we have crossed," because the crossing is now in the past tense. The alternative version is the one you are supposed to sing as you are waiting for the red light to turn green, and this one stats "We are waiting," and THIS is the one which ends with the prospect of the future, "we will cross."

I had, unthinkingly, been singing a jumbled version all the way back to the garage.

Usually, I don't sing that on the way home. Once we have taken the turnoff road to the top of the rise, I generally sing my very bad version of the MARSEILLAISE, confident that the likelihood of any French-speaking people being in earshot is vanishingly small.

Anyway, this entry provides a snapshot of a moment in a brain-damaged life. My own take on this particular entry is that the outcome is optimistic. I did, after all, finally triumphed (sort of) in my Confrontation with the Chair, though it was Chair 3, Hugh 0 foe part of the match.

To draw back now from the specifics of the chair and to look at my survivor's life in broad perspective, I can write as follows:

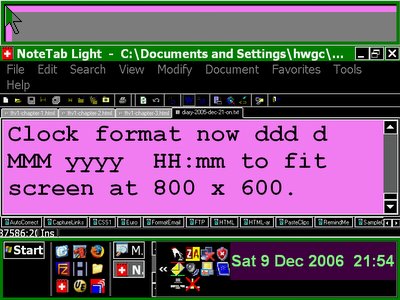

The reality of living with a damaged brain is that I can function well enough if I am following a routine. But learning anything new is painfully difficult. My existing skill set (teaching, talking, reading, writing and building HTML pages) is solid. But learning anything new, such as mastering the mechanics of the Silver Cross, is an exercise in frustration.

The good point is that I know that I can retrain myself. All it needs is patience and the will to persist.

I've always been a great one for plans and schedules and, living with brain damage, I've cultivated this habit, endeavoring to have my life run on rails as much as possible, always getting on exactly the same train at pretty much the same time and always taking, if possible, exactly the same seat.

And getting off at exactly the same place on the platform at Waniguchi, the station where Waniguchi Gakko is located. Exiting in just the right place to get at the drinking fountain.

I have avoided, then, adventures in innovation. Have avoided new challenges. But one has been schedule for me in January. I will go and be trained to teach the smallest kids that the company teaches, kids about the same age as my daughter.

My reading spectacles will not be adequate for that task because, while they allow me to read even the smallest print, they throw everything else out of focus.

So, Monday evening, the evening of the day on which I was informed that kids training was in my future, I hunted out my progressive spectacles. These things, a compromise pair of spectacles, are not so good for reading, but do provide me with a reasonable degree of focus over a range of distances, including the distances.

After having a pair of progressive lenses made, I abandoned their use because I found that, as a far-sighted person, which is what I am following the implantation of intraocular lenses to replace those that were removed by cataract surgery, progressive lenses are unsatisfactory.

But if I have to monitor a bunch of screaming kids and have to both read materials and keep track of small objects such as kids' balls flying loose, then my progressive lenses will be good enough for the purpose.

In summary, the reality of living with brain damage is that it's doable, but from time to time I hit situations which are extremely frustrating. That said, I can still cope with my life and go forward, and can cope with the fact that my short-term memory is faulty and that my capacity for night navigation seems to have been permanently deleted. Put me in the dark and I get completely lost, but my magnificent Maglite torch ensures that I am never left entirely in the dark.

Just a final note: this story has a happy ending. Monday I suffered defeat at the hands of the chair. Tuesday I succeeded. Sort of. Wednesday I was triumphant, collapsing the push chair effortlessly, and even succeeding in snugging it into a nice compact package then latching it shut with the built-in latch provided. I have become a master of the process.